It’s the government’s job to make it easier and cheaper for people to change their lives.

Keir Starmer’s pledge to cut the UK’s emissions by 81% by 2035 is undoubtedly ambitious. However, his assertion at the Cop29 climate conference that it can be achieved without “telling people how to live their lives” is probably not true – at least, not according to what scientists who study this problem have found.

We are two such researchers. Our work concerns the lifestyle and behaviour changes needed to mitigate climate change and we argue that Starmer’s claim is not only unrealistic, it’s also potentially harmful to the prospects of effective climate action.

Many politicians, including Starmer, subscribe to the belief that technological advancements alone – more efficient wind turbines or electric vehicle batteries – will solve the climate crisis. This kind of “techno-optimism” is rife in government policy statements and strategies, but it is misplaced.

The latest scientific assessments, and our own research, show that systemic changes to society and the global economy are necessary to keep global warming at safe levels. While some progress has been made in shifting the supply of energy from fossil fuels to renewables (in the UK, renewables now account for 40% of electricity generation, though only 25% of total energy), far less attention has been paid to tackling demand – how we use energy and resources – which directly relates to people’s lifestyles and values.

Radically different lifestyles

Telling people “how to live their lives”, or more accurately, encouraging and enabling significant lifestyle changes, is essential for meeting climate targets. Most measures for reaching carbon targets in the UK will require changes to public behaviour. It’s the government’s job to make it easier, cheaper and advantageous for people to make those changes.

The necessary scale of this change is startling. To stay within the emissions budget consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5°C, the average UK carbon footprint must shrink from the equivalent of 8.5 to 2.5 tonnes of CO₂ by 2030.

This cannot be achieved through incremental change. It requires radically different lifestyles which involve flying less, eating more plant-based foods, wasting less and replacing boilers and combustion engines with heat pumps and electric vehicles.

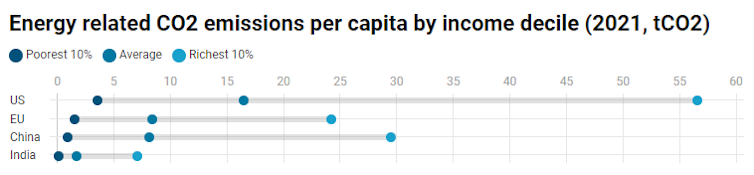

Not everyone needs to change their lifestyle to the same extent. Those with the largest carbon footprints – typically the wealthiest people – need to make the most significant changes. As well as having a moral responsibility to act, wealthy people also have a greater capability to change and have more potential to influence wider change as organisational leaders and investors.

Change for the better

Not all climate action is sacrifice. Pro-environmental behaviour and lifestyle change can improve your wellbeing.

There is overwhelming evidence that climate action has health benefits, whether it is eating more plant-based food and less meat, or enjoying cleaner air as you walk or cycle instead of driving.

People with greener lifestyles also tend to be happier. Our international analysis found people who took more environmental action reported higher wellbeing. It can also help manage anxiety about the climate. In this sense going green is more likely to improve your quality of life rather than diminish it.

Importantly, research from numerous countries shows that there is public appetite for radical change. This includes not just a desire for governments and businesses to do more to address climate change, but also a willingness to make personal sacrifices. In a survey of 130,000 people randomly selected across across 125 countries, 69% said they would be willing to contribute 1% of their personal income to climate action.

Achieving the necessary changes to our lives and wider society will require more than public information campaigns (“telling people how to live their lives”, as Starmer calls it). These are what we call downstream approaches: they urge people to make different decisions but have been shown to have little effect in changing behaviour in the long term.

Instead, we need upstream approaches which change the array of options available to everyone. This could involve using regulations, taxes and subsidies to make low-carbon lifestyles easier, cheaper and more attractive to adopt. Most of these measures already enjoy public support.

While Starmer’s emissions target is commendable, his reluctance to discuss lifestyle changes is at odds with the scientific consensus. Tackling climate change effectively requires a shift to a more equal society, where happiness is prioritised over consumption. It necessitates radical behavioural changes, particularly from the wealthiest, and policies that enable these changes.

This article is authored by Sam Hampton, Researcher, Environmental Geography, University of Oxford and Lorraine Whitmarsh, Professor of Environmental Psychology, University of Bath. It is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.